Q4: Incentives: The Power of Collaborative Structures

In Q3, we discussed how coordination at its finest is what makes large-scale ecosystems possible. Nonetheless, it is not necessarily what makes them preferred over other constellations. Here, the role of incentives and how they enable value creation to be a synergistic paradigm is integral to what ecosystems and their collaborative dynamics can accomplish. It’s worth noting that we’ve been moving in the more cooperative direction for some time, in large part due to our engagement with digital innovation.

Interconnectivity and The Role of Coordination

Looking back a few decades, even though some collaborations may have been seen as worthwhile for various reasons (resource management, enhanced product development, etc.), the cost of coordinating the involved parties around a particular mission or objective was very expensive. Think of the times when we had to use fax machines to exchange documents? Even more so, think of how companies coordinated before then, without computers or any ability to correspond without physical letters? Let’s just say some of what we’re up to nowadays would’ve been deemed wishful thinking.

Computers and their increased capabilities over time have changed the paradigm completely in this regard, yielding communication, knowledge sharing, supply chain and more, streamlined — to the point where it has changed how organizations need to work to excel. And none of this emerged purely from enhanced technological capabilities. Processes changed; new mindsets were embraced; unique dynamics were enforced. Over time, companies had to move from doing everything in-house (hierarchies) to aligning with the fact that partnerships and distributed creation were the better route (markets). It was cheaper, faster, and yielded better products, among other things.

Still, this never meant that hierarchies did not have a role to play. Hierarchies have long been the best alternative for products and services that are complex and have very specific demands/assets attached to them. However, over time, it’s been shown that ecosystems have the ability to push the envelope on this end as well. Just consider Apple’s 16-page long supplier list and what that tells you about the collaborative production of consumer electronics. Note that even Samsung — Apple’s direct competitor on the phone market — also frequently pops up as a supplier for them! Coordinating around this complexity is no longer a tall order, and for that reason, entire companies are created around building very specific things and supplying other companies with them. And, even more special, we now live in a world where competitors can equally be seen as collaborators.

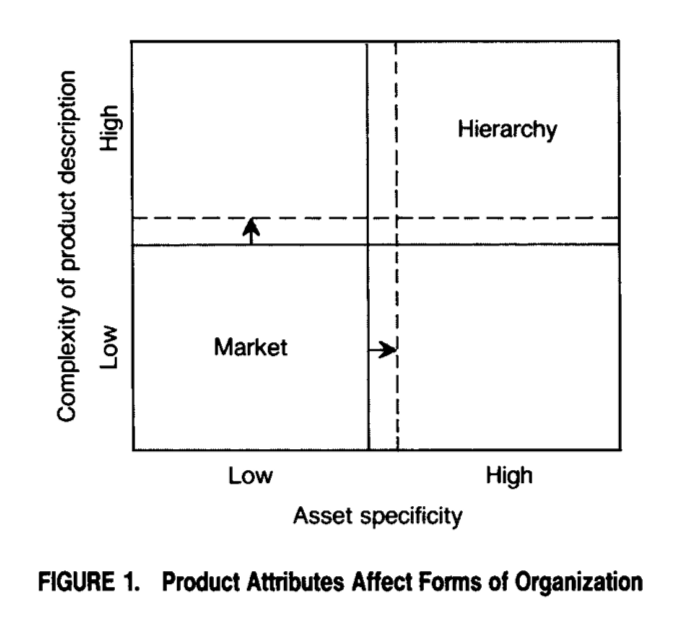

The arrows in Figure 1 below (from Malone et al. 1987) highlight the effect digital innovation (and better/cheaper coordination resulting from it) has on the extent to which distributed/horizontal approaches are preferred to in-house/vertical ones. The case we are making is that these arrows are still pushing our capabilities to gather around more interconnected market structures — which in turn set the precedent for more flexibility in how value is created. There is naturally a cap on how much markets can do, and how this development affects the future of work and production really depends on what we’re looking to optimize for (which there will be many opinions on) — but in either case, the new forms of mutual adjustment are moving us toward a paradigm where more and more can be done through better coordination. The right answer to what should be done is worth exploring — but the intuition is sustainably establishing more connections, way beyond what fits on a leading company’s supplier list.

The Expansion of Collaborative Incentives

The rise of digital innovation has kept us significantly expanding our coordination capabilities. Platforms, stronger algorithms for personalization, more processing power and better network infrastructure are all contributing toward a world that is more interconnected and interdependent than ever, on every level (individual, venture, society, and so on). This naturally has its respective caveats, but the point is that if interdependencies are managed in a streamlined and sustainable fashion — which we in Q3 highlighted as something we’re constantly getting better at — the possibilities are seemingly endless. This is what by some in academia is referred to as microfoundations, which in turn lead to dynamic capabilities for a larger ecosystem. At the very least, this development will lead us to embrace already existing distributed dynamics even further.

In the earlier days, taking on the new incentives made possible by digital innovation was an upfront investment in organizational change — but one often worth making to get the most out of the resources given. In fact, research shows how the economic growth that comes with information technology (IT) is often not experienced until after processes have been put in place to accommodate their potential. Back in 2000, we were talking years after deployment — not something every organization can afford or wait for.

Nonetheless, we’re now reaching a point where that investment is minuscule by comparison, and in some cases, companies are even in the business of making the organizational change as seamless as possible, many of whose offerings are free to use in some capacity (Google Suite, AWS, Github, Hubspot and Asana to name a few). If it’s cheaper, more efficient, and increasingly seamless to coordinate and collaborate with parties beyond the boundaries of one’s own organization, we will see more of it. And well, it keeps heading in that direction — which in turn keeps reducing the risk that comes with putting together ecosystems of various kinds. But this is likely only scratching the surface.

Our future prospects move us from being able to coordinate in instances where it’s an obviously worthwhile pursuit, to contexts where the intuition may say otherwise. In the examples we’ve discussed thus far, the benefit of collaboration was quite structured, and the parties engaging in it were established. However, if our ability to mutually adjust (and doing so cheaply) is significantly increasing, we have the opportunity to introduce incentives to less structured environments that previously have been difficult to target — including early-stage venture building and entrepreneurship, which FuzeQube considers a priority.

We will thus move toward coordination becoming increasingly predictable. Downside is small, upside is huge. We can increase the probability with which meaningful interactions seamlessly happen when we simply do not expect them to. This is where the value of AI becomes increasingly focal, gathering insights from the giant heaps of high-quality data at our disposal (if done right). Companies such as ecosystem.ai specialize in predicting what interactions will be perceived as meaningful by a given audience — a capability that will be key in defining the structures that are built around ecosystems to enable their dynamism. AI and its impact on our landscape likely deserves its own post, so do expect that in the weeks ahead.

Within organizations, collaborative dynamics are currently more prevalent than between them. Of course, you will never have these in equal measure (healthy competition is a thing!) — but how do we enable higher probabilities of meaningful interactions, regardless of whether these interactions are external or internal? Moving from asking the question of whether something gives a competitive advantage, to thinking more broadly about value generation and what it entails, poses a real challenge for our societal landscape and how we’ve been doing things since the industrial revolution (and perhaps even before).

Nonetheless, it equally presents a new opportunity, where our advances in coordination and IT let us expand on the incentives we are able to offer and facilitate. On the most basic level, the blockchain industry is actively attempting this with “to-earn” models, where individuals and groups are incentivized through tokenization and associated rewards to engage in various activities — often ones that may have had a higher barrier to return, such as playing video games, keeping your Bluetooth on, or even walking (yes, it’s good for your health — but have you ever made money doing it?). Blockchain and trustless systems will also be featured on here sometime soon.

Ecosystems have been useful to larger organizations and their production lines for decades. The picture we’re hoping this paints is how they now can be a resource almost across the board, independent of industry, org size, mission and vision — including in contexts where unleashing meaningful innovation is the key objective.

Creating Incentives for Meaningful Innovation

This reflection won’t give you the full picture, as it likely deserves more attention, but hopefully part of it. In the world of entrepreneurship and venture building, where competition is the default mode, building ecosystems when the incentives are not in plain sight is a tall order. Now, add the difficulty for a founder in putting a finger on what might be the most valuable addition to their organization at a given point in time, and you have major obstacles curbing innovation. This isn’t to say that ventures and founders don’t actively seek partnerships and resources — it’s all they do. However, the level at which it’s done often doesn’t line up with the prospects given to us by state-of-the-art coordination.

Just think of the resource management piece — how many startups end up reinventing the wheel with their processes, requirements and strategies, even when peers in the same industry have gone through the same hurdles? Sadly, I’m speaking from experience here. While building my previous company, a piece of information that everyone who has worked with metal-injection molding is aware of, and that we had completely missed, had me and my co-founder spend four months building features for our product that simply were not feasible and eventually got scrapped. As a startup, four wasted months can be the difference between survival and defeat, and yet we all too often engage in activities that others have gone through and strongly advised against (whether or not we may have been aware of it). The barriers to knowledge are perceived to be high, and thus the incentives to share knowledge across organizational boundaries are limited.

In such a context, I was the founder who would’ve needed to take a piece of advice. Equally relevant, other founders and practicioners (early-stage or beyond) are often incredibly constrained in terms of time and money, thus disincentivized to give said advice. They have unique insights but also limited bandwidth to share these findings with others who may need it — even if they actually want to! When they can, entrepreneurs pour their hearts into helping others and sharing their resources — it’s just that the constraints on them are real and palpable.

Even when incentives are prevalent, the symbiosis is not always mutualistic (see Q2!). Consider the relationships we see between venture builders and investors, where equity could serve as the incentive to drive a venture together. Founders, new and seasoned alike, will be very familiar with contemplating how much of their business they can give up to an investor. On one hand, you may benefit from a strategic partner to grow the venture with. On the other, the more you give up, the less control you have of the growth trajectory and — more critical — the vision. This is why very often, the right investment is not necessarily the biggest or the one that ensures the highest valuation. So, the incentives are not always aligned.

This may be trivial, but it becomes evident here that our perceptions of value encompass way more than revenue generation and profitability, even in the professional context. There are certain subjective prospects that trigger us to go beyond our comfort zones in the interest of a particular, unreasonably difficult mission — and it’s so, so special, as those who end up in this trance often create value in ways beyond everyone else’s imagination. The question is, how do you accommodate people and endeavors of that nature? You provide options that account for this diversity of perception and need.

This is where the power of platforms once again comes into play. They allow for many different assets and incentives to be made available to everyone in a way that does not subscribe them to all, but rather afford them a larger scope of possibility. This will allow us to embrace the notion of generativity, which largely posits that innovation and synergies can come from many different places, and that you’d want to keep those possibilities open. I’m sure this word will be given new meaning in the new era of generative AI, but in this context, I’m referring to Zittrain’s focus on “unanticipated change through unfiltered contributions from broad and varied audiences”, resulting from generative technologies like platforms.

I brought up Enquire as an example already in Q3, but I must highlight them again. Just think of how a combination of Enquire’s platform and marketplace can be used to not only unlock better knowledge sharing within and between organizations, but also to actively pay entrepreneurs and builders to share that knowledge? What incentive structures that work best will depend on scenario and nature of knowledge sharing (this is a big part of our consulting work), but point being that if sharing advice does not bite into a founder’s constraints, they’re more likely to do it. Hopefully it isn’t a controversial take to say we want to see more of that! It would’ve saved me four months, and ensured other startups their survival. I cannot overstate how much these resources mean to founders — but equally any organization that is serious about optimizing their operations and value generation.

These incentives can’t be unidimensional, though. In contexts of innovation, everything made available to organizations must be somewhat loosely coupled and not tied to excessive mandatory process. This is what often kills the generativity of a given initiative. How organizations then combine assets, incentives, and coordination mechanisms to create unique capabilities will be up to them — in fact, this will often be what enables a competitive advantage for ventures from the get-go, as the resource-based view of firms posits.

You also want these assets and incentives to be sustainable over time — which ironically means an ecosystem builder needs to have a giving mindset beyond what might seem intuitive. As is the case so often, gaming is taking a lead on this. Epic Games recently announced it will pay 40% of its revenues to creators, and Roblox has already paid out $500M to its developers and their open innovation platform. On the individual level, YouTube and TikTok have been doing the same for some time, in a more automated and streamlined fashion.

The incentives are also not always about money. In fact, it should be about diversifying resources to the point where entrepreneurs can find the right incentives for them — whether these are money rewards and tokenized assets for performing certain tasks, subsidized access to Enquire’s platform, or entry points to unique findings and people through ecosystem membership. As said, the possibilities are seemingly endless, and part of the key is simply to offer diverse options and opportunities, along with proper guidance and information on how to deploy them in a unique way that accomodates the conditions of founders and their respective ventures.

I will cap it here for now, as I fear I might dilute the message if I don’t, but to reiterate — this collaborative dynamic has a direct return. These are obviously not purely benevolent initiatives, as incentives of this kind are what enable people to build fantastic ventures, and to do so sustainably. It’s for these reasons that ecosystems became prominent constellations in the first place, and our technological and societal developments are pushing us further in that direction, mainstreaming ecosystems beyond what has been possible in the past. We’re beyond excited about these prospects, and the structures that will result from our mission of fueling meaningful innovation.

Nonetheless, only so much can be done through structures — the rest is all about people, as I may have hinted at throughout this piece. Hoping to elaborate on that next time!

Bardia Bijani

Managing Partner, FuzeQube Group