Q3: Coordination: how do ecosystems manage complexity?

In Q1, I tried to provide context to the complementary dynamics and characteristics of ecosystems (might be worth looking over if you need a refresher!). We’re taking a different route with this one by looking at what might hinder successful ecosystems — and much of it can be tied back to coordination and alignment of various forms. I’ll elaborate!

Complexity: Interdependency Challenges

We talked in Q1 about the value of putting consulting and technical implementation under the same roof to improve coordination. The other side of the coin is how this sort of bundling increases the extent to which the loosely coupled modules (in this case, consulting and implementation respectively) impact one another.

From a client’s standpoint, how much trust would they have in a company’s implementation if the strategy was perceived to be done poorly, and vice versa? Even more evidently, imagine having a supply chain where all components of a device are made available for assembly, except one… Think of how the global semiconductor chip shortage alone stopped in-demand hardware such as the Playstation 5 from reaching stores in reasonable quantities for almost two years!

Strengthened and more frequent complementarities may be the key to new forms of value generation and utility, but they equally require an increase in complexity which, if not managed correctly, can lead to fragile and volatile ecosystems. The strongest complementarities come with scaling of complexity, but scaling is difficult AND expensive. So, most organizations settle for weaker, lower-risk complementarities in the interest of less complexity and higher sustainability (and sometimes, rightfully so). For large ecosystems, as FuzeQube intends to be, that is not an option, which leaves us with a necessary responsibility: interdependency management.

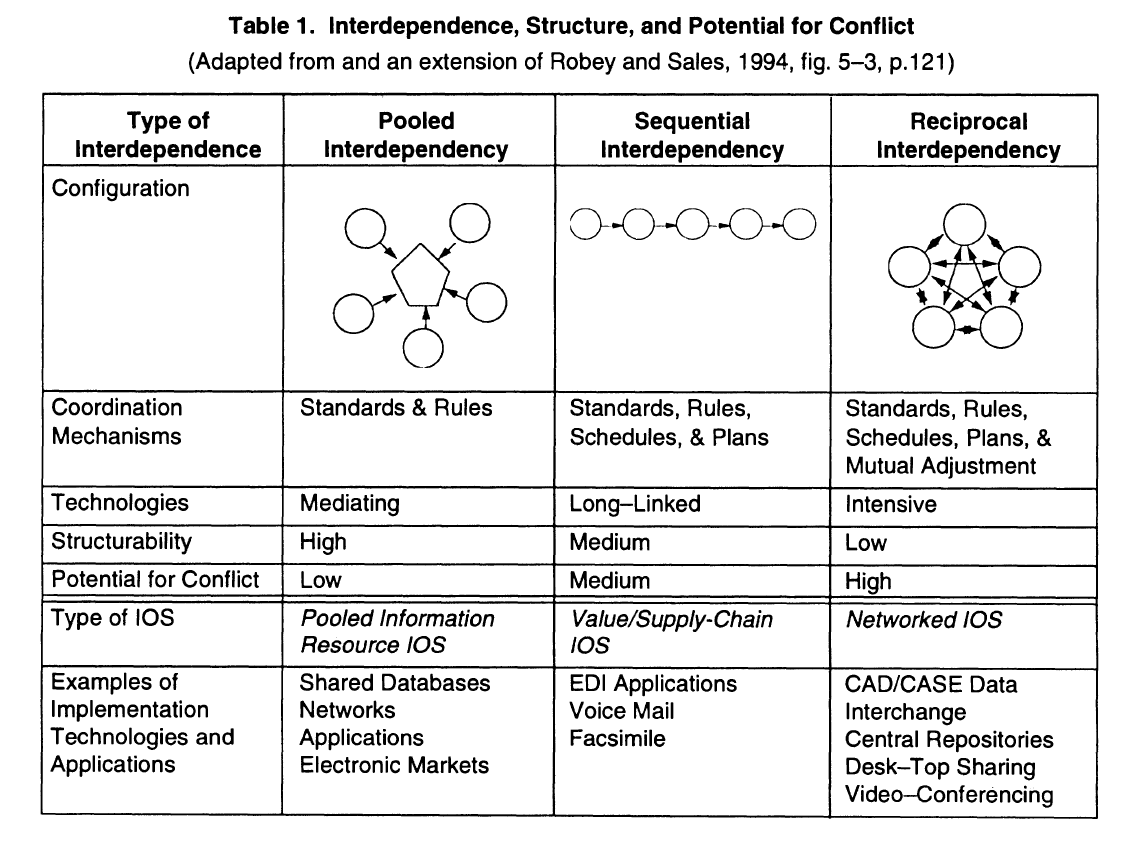

The concept of interdependence is often used as a representation or proxy for the sort of complexity we’re highlighting here. Thompson’s Organizations in Action (1967) outlines three types of interdependence, in ascending order of posed complexity. Kumar & Van Dissel (1996) do a good job of highlighting these, along with some other variables that may come in handy:

Figure 1. Interdependence table, taken from Kumar & Van Dissel (1996).

Yes, some of the examples are somewhat outdated, but hopefully you get the idea. Pooled interdependencies are independent of relationship to other actors — like how visiting a traditional website won’t stop someone else trying to do the same (unless we account for traffic limitations — ChatGPT, I’m looking at you!). Sequential interdependencies are unidirectional, like seen with the Playstation 5 supply chain issue from before — semiconductor manufacturers could stop Sony from making consoles, but the dependency doesn’t hold the other way around. And, last but certainly not least, reciprocal (or networked) interdependencies, where everything and everyone within a particular system impact one another — one person making changes to a widely shared Google Doc may be a good, basic example. The point is that depending on the type of interdependency, we can expect different levels of impact and complexity — and with that, different ways to best deal with those conditions.

Coordination Mechanisms and The Role of Information Technology (IT)

When discussing these three forms of interdependence, Thompson equally brings forth the processes or flows that are best suited to deal with each form. The coordination mechanisms, outlined in Figure 1 as standards/rules, planning/schedules and mutual adjustment, are key to this. Standardization and planning/schedules are somewhat self-explanatory in how they allow for coordination, as we see in our interdependency examples. Traditional websites are based around the notion that you want everyone to have access to the exact same thing (standardization), while Sony likely would’ve been better off with a more comprehensive plan around how to diversify semiconductor supply, and how drawbacks could affect their scheduled objectives.

Nonetheless, the way we look at coordination has changed a lot in the digital age. Information technology (IT) has made the enforcement of coordination mechanisms significantly more streamlined — in fact, interdependence management has been recognized as “IT’s most important role” by researchers. With that, the three coordination mechanisms set out by Thompson still seem to hold, but the way we express and deploy mutual adjustment is expanding through our interactions with technology and thus making new forms of value exchange possible. Ensuring that a Google Doc changes for everyone when one person makes a change — a prime example of basic mutual adjustment — might not come off as a biggie compared to Sony’s supply chain challenges, but that’s exactly what gets the point of IT and digital innovation across — the barriers to mutual adjustment are significantly lowered as a result of our interactions with it.

In fact, one of the main value propositions of the digital age is that we now, with ease, can use IT to finetune other coordination mechanisms through mutual adjustment — that is, the standards, rules, plans and schedules we just outlined. Workflow and task management platforms, like ServiceNow and Asana, are examples that streamline our operations by letting us plan and facilitate more flexibility for how relevant stakeholders interact with and act upon said plans — coordinating coordination, in some sense!

More importantly, this shows how we’re opening new doors to mutual adjustment. Platforms equip us with the powers of exploration and exposure by giving us all the options in the world, along with the necessary tools to zone in and find the best people and things for our context; AI enhances human bandwidth in unprecedented ways; blockchain lets us surmount trust barriers; immersive technologies give us experience and context at scale; and so on. It will be interesting to see how these possibilities, enabled by taking the consumer web from read-only (Web 1.0) to read-and-write (Web 2.0), will be even further enhanced through Web 3.0 (read + write + execute) — but that is a topic for another post! All this is to say that we have better, more effective methods of coordination to look forward to in the days to come. The question is if these capabilities alone will lead to the outcomes we seek.

Synergistic Incentives: where are they?

The more complex the interdependency, the less structurable it is and more conflict potential it has (as Figure 1 points out). Ecosystems need to manage interdependencies in a way that resembles how microservices are managed within an app or software package. Each service, or module, has its own set of isolated interdependencies, but equally some that translate into additional complexity beyond the module in question. This, if anything, necessitates assembly that isn’t managing complexity just for the sake of it — especially when it is genuinely difficult and taxing to manage. Although conflict in this context is often framed as a merely a logistical issue, there’s reason to believe it goes further than that, as logistics are inevitably influenced by motives. It is one thing to make a form of collaboration feasible — which digital innovation has helped us with plenty — but to also make it favorable (and frequently deployed as a result) is a different beast.

As outlined in Q2, favorable conditions and complementarities are not always easy to spot. When the objective is clear and tangible, ecosystems are easier to construct and align parties around. If a particular product, like a phone, being brought to market is what fuels the business of entities responsible for the necessary components, there are obvious incentives in place for the entities in question to “move together.” The notion of the holistic value generation exceeding that of the sum of the individual parts is quite evident here — in other instances, not so much.

AngelList and Acquire are two initiatives that do a great job of trying to enable these dynamics — and they succeed in many respects. These tools do exactly what good platforms are supposed to do — they make existing synergies more visible and thus meaningful interactions more probable. However, these synergies are some of the most inherent to traditional venture building — investment/fundraising and mergers/acquisitions, respectively. They do not necessarily enable or reveal unique types of synergies, or strengthen synergies already at hand.

This is where novel forms of mutual adjustment come through. These are manifested in ventures like Enquire, where the strengths and benefits are not purely derived from platform/network effects and access to a very large and diverse set of experts, but also through the alignment of incentives around a particular objective (in Enquire’s case, unique knowledge sharing — an essential activity for organizations, both internally and externally). These types of capabilities can further be leveraged by ecosystem builders, like FuzeQube, to highlight and encourage interactions of various kinds. This is part of what our proof of concept stage hopes to showcase — that necessary resources (human and technical) coupled with the right incentives lead to meaningful interactions at scale, and subsequently to impactful innovation at unprecedented rates.

In summary: there is immense value in deploying the coordination mechanisms of our time (and the future) to manage the complexity that comes with ambition — but equally these mechanisms require alignment with incentives that drive said ambition to be fully leveraged. So, one may then wonder: are synergistic incentives a necessity for better ecosystems? This is our next point of exploration.

Bardia Bijani

Managing Partner, FuzeQube Group